Nether Wallop Mill, Hampshire, England - 23 February 2018

I am still not exactly sure why we did it; it seemed like a good idea at the time. What would be so difficult about fishing the compass extremes of the world's chalkstreams? As it so happens, it is more problematic than you might expect.

|

|

Not a chalkstream?

|

Now, I think (all modesty

aside) I

know a thing or two about our unique rivers but finding the most northerly,

easterly, westerly and southern examples was more challenging than I expected.

Do you define by where an

individual river starts or where it finishes? Or perhaps by where the arc of

its flow takes it. How do you classify a river that starts as a chalkstream but

ends as something else? And if you do, where exactly is that point of

difference? Are maps the definitive guide to each and every chalkstream? Not

always. Are some so small as to be just technically a river? A trip took me to

the Isle of Wight where I could barely see the Cawl Bourne even though I was on

the bridge that straddled it. Was there any point fishing a river that was

patently unfishable? And most importantly how do you precisely define a

chalkstream?

On that last question I was

extremely fortunate to have the assistance of the Environment Agency's expert

Lawrence Talks and writer/conservationist Charles Rangeley Wilson. Both have

done many years of research on precisely this question, with maps and lists of

the English chalkstreams. There were a few points of difference but in the end

finding where to head - Yorkshire to the north, Dorset to the west and Norfolk

to the east - was relatively easily decided, give or take a few topographical

compromises. But as for the south ......

Now everyone wants to claim

a chalkstream; it is marketing gold. So, you'll find claims staked in New

Zealand, Russia, Slovenia, Belgium, Switzerland and Germany, plus plenty more I

probably never came across. I am sure many of these simply arise from mistaken

identity, plus a dose of wish fulfilment, for there are a great many rivers

that look and act like a chalkstream but are, in one or more important

characteristic, not the real deal. If you start from the basic premise "the

technical definition of a chalk stream is any river whose base-flow index (the

volume of river flow derived from groundwater aquifers) exceeds 75%, and whose

course runs over chalk geology" you will get some idea of the geographical

complexities involved.

|

|

Extent of English chalkstreams

|

The fact is chalkstreams only

exist in two countries: England and France, the latter containing somewhere in

the region of a dozen. Unfortunately for me there was no French equivalent of

the EA or the Delphic voice of Rangeley Wilson to guide me. The best source I

could find was a tour of French rivers by English Nature in 2003 which starts

with the less than inspiring aim, and I quote, of 'understanding how rivers -

particularly SAC rivers nominated by Member States under EC Directive 92/43 -

are managed and protected in France'. It was useful but far from definitive.

Again and again in the

research I ran into the same problem - it looks like a chalkstream but it isn't

a chalkstream. I am sure plenty of you have travelled around Provence in the

south of France and admired the gorgeous limestone rivers in towns like

L'Isle-sur-la-Sorgue (pictured). But they are exactly that - limestone rivers

where the water arrives through fissures in the rock rather than being first

absorbed into porous chalk. It makes a difference. Often you'll notice a slight

'milkiness' to a limestone river which is in fact tiny particles of limestone

that the chalk would otherwise filter out.

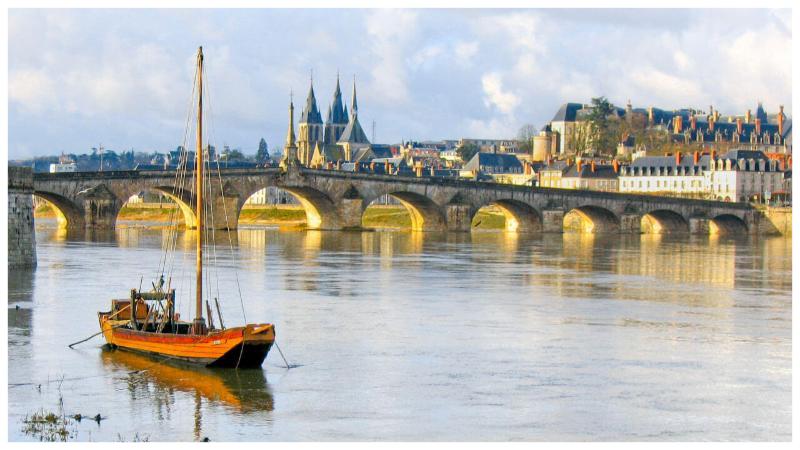

So, I turned my thoughts

back north to concentrate on the well-known chalkstreams of Normandy such as

the Risle, a favourite of Frank Sawyer, and the Andelle. They seemed a good

enough solution but something kept nagging at me - champagne. If you travel

around the villages surrounding Stockbridge these days you'll see thousands of

acres of recently planted grape vines since it has been discovered that our

chalk downs are the geological twin of the Champagne region.

Actually it is wrong to call

them a twin, for one is really the continuation of the other. The chalk ground

that the Pinot Noir grape and the other two varieties favoured in champagne

making like to grow on is part of a seam that starts in Yorkshire, runs down

the east coast, jinks south west, disappears under the Channel (hence the Cawl

Bourne on the Isle of Wight) to reappear in Normandy until it finally peters

out in the Champagne region. And the river that follows more or less along the

Gallic leg is none other than the River Seine. All 482 miles of it. Could it be

that the river that runs through the centre of Paris is really the southernmost

chalkstream in the globe?

Next time in part 2: First

stop Yorkshire

RABBITS

BREED CONTROVERSY

Who knew rabbits could be so controversial? In the last quiz I

asked, 'Who imported the rabbit to the British Isles?' and gave the answer,

'The Normans from what is now northern France in the 12th century.'

Plenty of people

subsequently pulled me up, pointing out that the Romans had bought rabbits

to Britain and you are all entirely correct. The question I had intended to set

was who introduced rabbits to the wild (the

|

|

Rabbit brooch. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

|

Roman ones were

domesticated) and hence my answer. It is generally accepted that had rabbits

existed in the UK between the Romans and the later introduction they would have

been noted in some form or another in the Domesday Book of 1085.

However, just

when you thought it was safe to put this one to bed I came across yet further

research that may prove all the above could well be wrong as it seems we have

proof rabbits lived here long before the Romans set foot on British soil as

remains of rabbits dating back half a million years were found at Boxgrove in

West Sussex and Swanscombe in Kent during digs in the 1980's and 1990's.

Palaeontologist

Simon Parfitt of the Natural History Museum, who worked on the Boxgrove dig, is

quoted as saying:

'We found all

sorts of animals - from the tiny ones like shrews and bats to huge ones like

elephants. All of these animals were living in the landscape and were buried

together. We also found remains of hares, and a rabbit's tooth. This was quite

a surprise, as previously the idea had been that rabbits were living in the

Mediterranean coastal regions - around Spain, Southern France and Italy. We

don't know if humans were eating the rabbits at this time - there's no evidence

of that yet.'

There is a very

long time gap between the Boxgrove and Swanscombe rabbits and the Roman

rabbit... almost half a million years. As far as we know no evidence has been

found of rabbits existing in Britain between those two dates. So what happened?

Probably the last Ice Age.

PHOTO

& VIDEO OF THE MONTH

Photoshop

magic? No.

Photoshop

magic? No.

This is what happens when a

shark catches up with the bonefish on the end of your line. This was all that

was left of my friend's 7-9lb bone on a recent trip to East End Lodge in the

Grand Bahamas. I rather like the sort of perplexed look in the eye of the fish

that seems to be saying, "Is this really happening to me?"

And as for the video

, well I think

we may have got off rather lightly with just a shark .........

QUIZ

Hopefully I

have it all correct this time! As ever, all just for fun and the answers at the

bottom of the page.

1) Which is the longest river

entirely in France?

1) Which is the longest river

entirely in France?

2) Alba is the ancient name for

which country in Great Britain?

3) The Latin name Galanthus translates to milk

flower. What plant is this?

Have a good weekend.

Best wishes,

Simon Cooper simon@fishingbreaks.co.uk

Founder & Managing Director

Quiz answers:

1) The

Loire at 629 miles

2) Scotland

3) Snowdrop

Ten of thousands of houses have, or are being built, within what used to be regarded as Alresford's rural catchment. Now that is progress but when concrete replaces grass nature suffers. Rivers are sucked of water as aquifers are plumbed for domestic supplies. Of course the water doesn't 'disappear' but when it does return to the river it is as unclean run off or less-than-pure treated sewage water. In the short term a river can stand that, but in the long term? Well, think of it a bit like your garden - for a while it might survive if only watered by your washing up water, but in the end ...... Agriculture has also had a huge impact for in the 20th century it went from chemical free to chemical dependent; all manner of farming practices and crops, entirely absent or alien to the English countryside in previous centuries have become common currency.

Ten of thousands of houses have, or are being built, within what used to be regarded as Alresford's rural catchment. Now that is progress but when concrete replaces grass nature suffers. Rivers are sucked of water as aquifers are plumbed for domestic supplies. Of course the water doesn't 'disappear' but when it does return to the river it is as unclean run off or less-than-pure treated sewage water. In the short term a river can stand that, but in the long term? Well, think of it a bit like your garden - for a while it might survive if only watered by your washing up water, but in the end ...... Agriculture has also had a huge impact for in the 20th century it went from chemical free to chemical dependent; all manner of farming practices and crops, entirely absent or alien to the English countryside in previous centuries have become common currency.

I am not sure when Ellen DeGeneres, American stand-up comedian, sitcom actress and latterly a hugely successful TV chat show host actually said this but it made me laugh out loud.

I am not sure when Ellen DeGeneres, American stand-up comedian, sitcom actress and latterly a hugely successful TV chat show host actually said this but it made me laugh out loud.  The bleak February countryside, shorn of all cover, is a great time to watch the local residents going about daily survival. These are who I see from my desk as I write this. As ever, all just for fun and the answers at the bottom of the page.

The bleak February countryside, shorn of all cover, is a great time to watch the local residents going about daily survival. These are who I see from my desk as I write this. As ever, all just for fun and the answers at the bottom of the page.