Hares in danger

You see a

great many corpses beside the road at this time of year as the animal hierarchy

redistributes itself ahead of winter.

Badgers are so commonplace

as to not raise comment. Deer something to steer around. Grey squirrels

inexplicably more frequent that you might expect. But the saddest of all for me

are hares, the white, jagged broken bones of those strong rear legs poking out

of that beautiful golden brown fur. So, knowing how the population is in

decline, it made me sadder still when I read this week that myxomatosis, the

disease that wiped out 99% of the British rabbit population when deliberately

introduced in 1952, may have crossed over into the previously immune brown hare

population.

Hares have long been one of

my favourite British animals. They are, a bit like otters, remarkably strong

and large with a propensity to range far across large tracts of countryside

doing their best to avoid people, conducting their lives out of the sight of

humanity. For centuries they had made the empty downlands, where the greatest

disturbance was a few sheep, their home. But in the post-war drive for more

home food production, ploughs bit into land untouched by man since it was

exposed by the retreating ice cover millions of year ago. The places they lived

and the grassland they lived off has been disappearing ever since, the marginal

habitat they are forced to inhabit polluted by agricultural chemicals.

Hares have long been one of

my favourite British animals. They are, a bit like otters, remarkably strong

and large with a propensity to range far across large tracts of countryside

doing their best to avoid people, conducting their lives out of the sight of

humanity. For centuries they had made the empty downlands, where the greatest

disturbance was a few sheep, their home. But in the post-war drive for more

home food production, ploughs bit into land untouched by man since it was

exposed by the retreating ice cover millions of year ago. The places they lived

and the grassland they lived off has been disappearing ever since, the marginal

habitat they are forced to inhabit polluted by agricultural chemicals.

Sound familiar? You'll have

read something similar to describe the plight of water voles, song birds and

hedgehogs. In the case of hares it is estimated that the population has gone

from something above 4 million a century ago to 800,000 today. The worry is

that myxomatosis will all but wipe out the remaining hare population. However,

as ever with these stories the headline may not tell the whole story: nobody is

as yet certain that the unexplained deaths of hares in East Anglia are directly

attributable to myxomatosis. In the 1930's Australian scientists tried to

deliberately infect brown hares with the myxoma virus but failed. There have

been similar deaths in Spain but the evidence is inconclusive. In Ireland,

where hares are relatively more populous but myxomatosis incidence is of a similar

level to the UK, there have been no reported deaths.

Myxomatosis is spread by the

rabbit flea that carries the virus, infecting the rabbits by biting as they hop

from one host to the next; mortality once infected is close to a 100% as the

rabbits go blind, lose fur to ulceration and the body organs shut down. As you

might imagine in the close confines of a warren the fleas are easily

transferred, so populations are rapidly wiped out. Hares however live a

different life which suggests myxomatosis would not so easily take hold.

Brown hares prefer the

solitary life, living in very exposed habitats so they may use their acute

sight and hearing to avoid their primary predators - foxes and raptors - by

running at up to 45mph, which is faster than a horse. Unlike rabbits hares live

in the open, creating 'forms', small depressions in the ground among long

grass. Here they spend their day moving out to feed in the open at night.

Tender grass shoots, including cereal crops, are their main foods. Breeding takes

place between February and September with the young, known as leverets, born

fully furred with their eyes open who are then left by the mother in forms a

few yards from their birth place. Once a day for the first four weeks of their

lives, the leverets gather at sunset to be fed by the female, but otherwise

they receive no parental care. This avoids attracting predators to the young at

a stage when they are most vulnerable. They don't live particularly long lives,

3 to 4 years is the norm, with disease and predation the two major causes of

death.

This difference in

lifestyle, and in the absence of any firm evidence, has suggested by some that

the culprit may be rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD) which first emerged in

China in the 1980's. It has since spread around the globe first reaching

Britain in 1992 when the domestic rabbit infected the wild population. But RHD

is more virulent than myxomatosis wiping out 10m rabbits in 8 weeks when the

virus escaped quarantine on the 20km2 Wardang Island off the south

coast of Australia in 1995, spread as it is by contamination and the wind.

So for the moment, despite

many assumptions, we don't really know what is happening. The University of

East Anglia, along with the Suffolk and Norfolk Wildlife Trusts are trying to

gather dead hares for analysis but it is all certainly very odd. One report was

of six dead hares in a single field; for a solitary mammal that would be quite

a conclave. I suspect we have a while to go before we get to the bottom of this

particular problem but even when we do it won't change the truth: disease or no

disease, we are gradually, just a little at a time, destroying the British

countryside that we purport to love.

A 50th

celebration

Two weeks

ago I was so pleased to host a very special lunch at Nether Wallop to celebrate

the 50th

anniversary

of fly fishing at The Mill.

The guests of honour were

Renée Wilson, widow of Dermot Wilson, and their son Fergus. As Renée said to me

they were initially hesitant at accepting my invitation; neither had been to

The Mill since 1982 and the thought of a return stirred up all kinds of

memories. But as it turned out we all had the most wonderful time reminiscing

about Dermot, the wonderful camaraderie of the customers and the whole madness

of the venture he set his family on.

The guests of honour were

Renée Wilson, widow of Dermot Wilson, and their son Fergus. As Renée said to me

they were initially hesitant at accepting my invitation; neither had been to

The Mill since 1982 and the thought of a return stirred up all kinds of

memories. But as it turned out we all had the most wonderful time reminiscing

about Dermot, the wonderful camaraderie of the customers and the whole madness

of the venture he set his family on.

Charles Jardine, back then a

perm-haired recently graduated art student, joined us as he had been the

resident trainee guide/instructor under the guidance of the irascible Jim

Hadrell. Barrie Welham, a long time friend of Dermot and Renée was there,

producing a copy of the 1971 Trout & Salmon (cover price 17.5p!) which

featured the British record rainbow trout that he had just captured from The

Mill lake. Neil Patterson, he of Chalkstream Chronicle fame, read a

letter that Dermot had written to him apologising, in the most charming of

words, for inadvertently taking credit for a pattern Neil had invented. Richard

Banbury showed us where his desk had been in the days when Orvis took over The

Mill from Dermot and Renée.

We rounded the day off

unveiling a blue plaque that I hope will remain for many decades as a fitting

tribute to a great man.

|

Diane

Bassett. Richard Banbury. Fergus Wilson. Renee Wilson. Charles Jardine.

Barrie Welham. Neil Patterson

|

A troika of greats

I was

very touched as Renée Wilson handed me a gift wrapped package by way of thanks

for the day. As I undid the wrapping in her very understated way she said,

'These are just a few bits and pieces from Dermot's collection I thought you

might like.' I was overwhelmed when she told me the provenance of each of the

three items.

The first is one of Dermot's

very own reels. As the original UK Orvis dealer he was very loyal to the brand

who, you might be surprised to hear, actually made all their high-end reels in

the UK as late as the 1980's.

The first is one of Dermot's

very own reels. As the original UK Orvis dealer he was very loyal to the brand

who, you might be surprised to hear, actually made all their high-end reels in

the UK as late as the 1980's.

Renée tells me Dermot was a

bit obsessive, tagging everything, hence the label. The reel still has the

leader from the last time he fished.

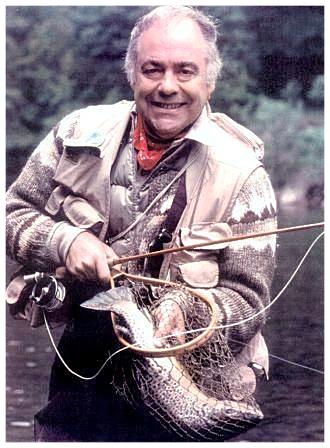

The net was a gift from the

legendary Lee Wulff, he of Gray Wulff fame, who was a regular visitor to The

Mill.

The final item is a fly box

full of flies that were tied by Ernie Schwiebert an American angling literary

colossus. He was a great friend of Dermot, the box a gift from him to Dermot

when they fished together in Montana.

Schwiebert is not so well

known in the UK but though I never met him I owe him a huge debt. He wrote a

two volume master work on trout in which, as a schoolchild, he enraptured me

about the chalkstreams. They were so much the weft and weave of my upbringing

that it took an outsider to show me how very special they were.

The quality of his writing

is without measure. Let me quote from a speech he gave in 2005, shortly before

his death. It is the very definition of why we fish.

|

|

Ernie Schwiebert

|

"People often ask why I

fish, and after seventy-odd years, I am beginning to understand.

I fish because of Beauty.

Everything about our sport

is beautiful. Its more than five centuries of manuscript and books and folios

are beautiful. Its artefacts of rods and beautifully machined reels are

beautiful. Its old wading staffs and split-willow creels, and the delicate artifice

of its flies, are beautiful. Dressing such confections of fur, feathers and

steel is beautiful, and our worktables are littered with gorgeous scraps of

tragopan and golden pheasant and blue chattered and Coq de Leon. The best of

sporting art is beautiful. The riverscapes that sustain the fish are beautiful.

Our methods of seeking them are beautiful, and we find ourselves enthralled

with the quicksilver poetry of the fish.

And in our contentious time

of partisan hubris, selfishness, and outright mendacity, Beauty itself may

prove the most endangered thing of all."

Quiz

The usual

random selection of questions to confirm or deny your personal brilliance. As

ever it is just for fun with the answers at the bottom of the page.

The usual

random selection of questions to confirm or deny your personal brilliance. As

ever it is just for fun with the answers at the bottom of the page.

1) What is the Latin numeral

for fifty?

2) Who are on the rear of the

current £50 note?

3) In what year did Queen

Elizabeth II celebrate her 50th year on the throne?

Enjoy the

weekend.

Best wishes,

Simon Cooper simon@fishingbreaks.co.uk

Founder & Managing Director

Quiz answers:

1)

L

2) Matthew

Boulton and James Watt, 18th century makers of steam engines

3) 2002. Makes

you feel old ........