Friday January 31st 2014

|

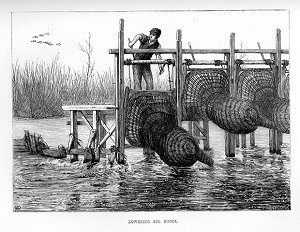

| Leckford eel traps |

Eels: chalkstream denizens in danger

I often walk by the eel traps at Leckford; if you are familiar with them you will do, like I, a double take. Where has the hut iconic hut gone? Don't despair, it is all part of a restoration, albeit a dramatic one, by the owners John Lewis of Waitrose fame.

The eels traps have always been part of the River Test scenery and though long disused, they make perfect sense to me. However, not everyone knows what they are about and falling into conversation with first-time visitors there are all kinds on fancy theories. Naturally, some kind on salmon capture device is high on the list of possibilities, which is not so far from the truth. Otter traps get a regular outing or crayfish, which again is not so ridiculous, as the baskets bear a resemblance to traps for them. I guess some people don’t realise the cages are lowered into the water to operate, which might explain why plenty of people think they are traps for kingfishers, ducks or swallows.

But the truth is that a century and a half ago the eel harvest was big, big business. In the time before refrigerated transport eels were much sought after as fresh meat, living as they do for days out of water. The so called Sprat & Winkle steam railway line that ran from Southampton to join the main London line passed along what is today the Test Way, provided an easy route to an eager and profitable market.

I say the salmon theory is not so far from the truth because eels, like salar, are part of the great migration to and from the chalkstreams across thousands of miles of Atlantic Ocean. Eels are extraordinary; born in the Sargasso Sea a few hundred miles off the coast of Florida they drift back towards the English coastline on the North Atlantic Current, growing from half an inch to two inches. Sniffing out the freshwater rivers they head upstream in summer, haul themselves out and cross the water meadows to find a damp ditch or pond to live out the next fifteen or twenty years. I know, it seems an extraordinary length of time to live in that one spot, but that they do, putting on an inch or so of growth each year.

Eventually the time comes to leave, so the eel retraces the route back to

the river (they have a remarkable sense of smell) and head downstream towards the sea and it is at this point during the summer months that the eel trap is sprung. Lowered into the water across the width of the river and at night, the time eels like to run, the ‘eel bucks’ as the traps should be termed, capture the eels that swim through the funnel-shaped entrance to become trapped at the point of the basket from which they cannot escape. For those who make it past the traps the English Channel beckons, before turning into the Bay of Biscay and then west to be carried on the North Equatorial Current back to the Sargasso Sea, were emaciated having not eaten since re-entering salt water on the year-long journey, they will spawn and die.

The Leckford traps, like their counterparts on the Thames, Severn and numerous other rivers, fell into disuse in the early 20th century when the working classes largely stopped eating eels with the proliferation of other fresh food. But sadly even if there was demand the declining eel population might not be able to support it. Since the 1980’s it is estimated that across Europe as a whole the population has declined by 95%. In Britain the situation is not quite as bad at 70%, but this in itself is a crisis figure with the European agencies seeking to find the causes of the decline which are likely a combination of changing ocean currents, temperature fluctuations and a fatal virus particular to eels that has spread from the southern hemisphere.

You can see the Leckford eel traps where The Bunny crosses the River Test. Here is the

Google map link; I highly recommend The Peat Spade Inn for lunch.

No comments:

Post a Comment